Notice of West building lobby closure at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford

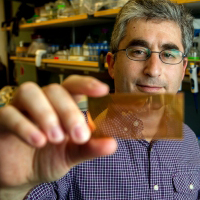

Stanford Researchers Invent Nanotech Microchip to Diagnose Type-1 Diabetes

For Release: July 14, 2014

STANFORD, Calif. – An inexpensive, portable, microchip-based test for diagnosing type-1 diabetes could improve patient care worldwide and help researchers better understand the disease, according to the device's inventors at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Described in a paper to be published online July 13 in Nature Medicine, the test employs nanotechnology to detect type-1 diabetes outside hospital settings. The handheld microchips distinguish between the two main forms of diabetes mellitus, which are both characterized by high blood-sugar levels but have different causes and treatments. Until now, making the distinction has required a slow, expensive test available only in sophisticated health-care settings. The researchers are seeking Food and Drug Administration approval of the device.

"With the new test, not only do we anticipate being able to diagnose diabetes more efficiently and more broadly, we will also understand diabetes better - both the natural history and how new therapies impact the body," said Brian Feldman, MD, PhD, assistant professor of pediatric endocrinology and the Bechtel Endowed Faculty Scholar in Pediatric Translational Medicine. Feldman, the senior author of the paper, is also a pediatric endocrinologist at Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford.

Better testing is needed because recent changes in who gets each form of the disease have made it risky to categorize patients based on their age, ethnicity or weight, as was common in the past, and also because of growing evidence that early, aggressive treatment of type-1 diabetes improves patients' long-term prognoses. Decades ago, type-1 diabetes was diagnosed almost exclusively in children, and type-2 diabetes almost always in middle-aged, overweight adults. The distinction was so sharp that lab confirmation of diabetes type was usually considered unnecessary, and was often avoided because of the old test's expense and difficulty. Now, because of the childhood obesity epidemic, about a quarter of newly diagnosed children have type-2 diabetes. And, for unclear reasons, a growing number of newly diagnosed adults have type-1.

Type-1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease caused by an inappropriate immune-system attack on healthy tissue. As a result, patients' bodies stop making insulin, a hormone that plays a key role in processing sugar. The disease begins when a person's own antibodies attack the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. The auto-antibodies are present in people with type-1 but not those with type-2, which is how tests distinguish between them.

A growing body of evidence suggests that rapid detection of, and aggressive new therapies for, type-1 diabetes benefit patients in the long run, possibly halting the autoimmune attack on the pancreas and preserving some of the body's ability to make insulin.

The old, slow test detected the auto-antibodies using radioactive materials, took several days, could only be performed by highly-trained lab staff and cost several hundred dollars per patient. In contrast, the microchip uses no radioactivity, produces results in minutes, and requires minimal training to use. Each chip, expected to cost about $20 to produce, can be used for upward of 15 tests. The microchip also uses a much smaller volume of blood than the older test; instead of requiring a lab-based blood draw, it can be done with blood from a finger prick.

The microchip relies on a fluorescence-based method for detecting the antibodies. The team's innovation is that the glass plates forming the base of each microchip are coated with an array of nanoparticle-sized islands of gold, which intensify the fluorescent signal, enabling reliable antibody detection. The test was validated with blood samples from people newly diagnosed with diabetes and from people without diabetes. Both groups had the old test and the microchip-based test performed on their blood.

In addition to new diabetics, people who are at risk of developing type-1 diabetes, such patients' close relatives, also may benefit from the test because it will allow doctors to quickly and cheaply track their auto-antibody levels before they show symptoms. Because it is so inexpensive, the test may also allow the first broad screening for diabetes auto-antibodies in the population at large.

"The auto-antibodies truly are a crystal ball," Feldman said. "Even if you don't have diabetes yet, if you have one auto-antibody linked to diabetes in your blood, you are at significant risk; with multiple auto-antibodies, it's more than 90 percent risk."

Type-1 diabetes patient Scott Gualdoni of Palo Alto, Calif., and his 9-year-old daughter, Mia, are excited about the new test. Gualdoni was diagnosed with diabetes in 2011, at age 41. Because of his age, his primary care physician began treating him for type-2 diabetes without testing him for auto-antibodies.

After a few months, Gualdoni returned to his doctor and asked for an antibody test. "I was just feeling like something wasn't right," he said. His suspicions were confirmed: He had type-1.

"Doctors may not be thinking adults can get late-onset type-1," he said. "I slipped through the cracks." He's eager to see the microchip test implemented because a cheap handheld test in the doctor's office would have saved him months of incorrect treatment. "If you're not treating the right disease, you're really doing damage to your body," he said.

The test also holds promise for Mia, who was found to have five kinds of diabetes auto-antibodies in her blood when she volunteered for TrialNet, a nationwide study that tracks relatives of people with type-1 diabetes to monitor their risk.

"I'm really excited for other people who are at high risk for diabetes that this new technology is available for them now," Mia said.

"There is great potential to capture people before they develop the disease, and prevent diabetes or prevent its complications by starting therapy early," Feldman said. "But the old test was prohibitive for that type of thinking because it was so costly and time-consuming."

Stanford University and the researchers have filed for a patent on the microchip, and the researchers also are working to launch a startup company to help get the method approved by the FDA and bring it to market, both in the United States and in parts of the world where the old test is too expensive and difficult to use.

"We would like this to be a technology that satisfies global need," Feldman said.

Research credits

Bo Zhang, a graduate student in chemistry, and Rajiv Kumar, MD, clinical assistant professor of pediatric endocrinology and diabetes, are lead authors of the paper. Another Stanford co-author is Hongjie Dai, PhD, professor of chemistry. Feldman and Dai are members of Stanford's Child Health Research Institute.

The work was supported by grants from Stanford's SPARK program; the National Institutes of Health (grant DP2OD006740); the National Cancer Institute (grant 5R01CA135109); JDRF, a type-1 diabetes research foundation; Stanford Bio-X; Genentech; and the Child Health Research Institute at Stanford.

Information about Stanford's Department of Pediatrics, which also supported the work, is available at http://pediatrics.stanford.edu.

Authors

Print media contact:

Erin Digitale

(650) 724-9175

digitale@stanford.edu

Broadcast media contact:

Margarita Gallardo

(650) 723-7897

mjgallardo@stanford.edu

About Stanford Medicine Children's Health

Stanford Medicine Children’s Health, with Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford at its center, is the Bay Area’s largest health care system exclusively dedicated to children and expectant mothers. Our network of care includes more than 65 locations across Northern California and more than 85 locations in the U.S. Western region. Along with Stanford Health Care and the Stanford School of Medicine, we are part of Stanford Medicine, an ecosystem harnessing the potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education, and clinical care to improve health outcomes around the world. We are a nonprofit organization committed to supporting the community through meaningful outreach programs and services and providing necessary medical care to families, regardless of their ability to pay. Discover more at stanfordchildrens.org.

About Stanford University School of Medicine

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation’s top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit med.stanford.edu/school. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Health Care and Stanford Children’s Health. For information about all three, please visit med.stanford.edu.

Connect with us:

Download our App: