Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Children

What is developmental dysplasia of the hip in children?

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a health problem of the hip joint. It’s when the joint hasn’t formed normally, so it doesn’t work as it should. DDH is present at birth. It is more common in girls than boys.

In a normal hip joint, the top (head) of the thighbone (femur) fits snugly into the hip socket. In a child with DDH, the hip socket is shallow. As a result, the head of the femur may slip in and out. This means it moves partly (subluxate) or completely (dislocate) out of the hip socket.

What causes DDH in a child?

A combination of things may lead to DDH. It may be partly genetic. DDH tends to run in families. It may also be partly environmental, such as:

Low amniotic fluid during pregnancy

A tight uterus that makes it hard for the fetus to move around, or a first born baby

A breech delivery, when the baby is born bottom first instead of headfirst

Which children are at risk for DDH?

First-born babies are at higher risk because the uterus is small and there is limited room for the baby to move. That may affect how the hip develops. Other risk factors are:

Family history of DDH, or very flexible ligaments

Position of the baby in the uterus, especially the breech position

Other orthopedic problems, such as clubfoot

Female sex. DDH is more common in girls than boys.

What are the symptoms of DDH in a child?

The following are the most common symptoms of DDH. Symptoms can occur a bit differently in each baby. They can include:

The leg may appear shorter on the side of the dislocated hip

The leg on the side of the dislocated hip may turn outward

The folds in the skin of the thigh or buttocks may appear uneven

The space between the legs may look wider than normal

The symptoms of DDH may seem like other health problems of the hip. Make sure your baby sees their healthcare provider for a diagnosis.

How is DDH diagnosed in a child?

DDH is sometimes noted at birth. A healthcare provider screens newborn babies in the hospital for this hip problem before they go home. But DDH may not be discovered until later checkups.

Your baby’s healthcare provider makes the diagnosis of DDH with a physical exam. During the exam, they ask about your baby’s birth history and whether other family members have DDH.

Your baby may also need these tests:

X-rays. This test makes images of internal tissues, bones, and organs.

Ultrasound (sonography). This test uses high-frequency sound waves and a computer to make images of blood vessels, tissues, and organs. It is used to view internal organs as they function and to assess blood flow through various vessels.

How is DDH treated in a child?

Treatment will depend on your baby’s symptoms, age, and general health. It will also depend on how bad the condition is.

The goal of treatment is to put the head of the femur back into the socket of the hip so that the hip can develop normally. Treatment choices vary for babies. They may include:

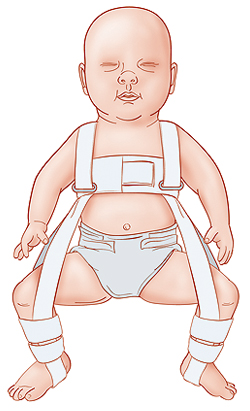

A special brace or harness. The Pavlik harness is most often used. It is used on babies up to 6 months of age to hold the hip in place while allowing the legs to move a little. Your baby’s healthcare provider puts the harness on and periodically checks its fit. The harness may fix the DDH. But sometimes the hip may still be partly or completely dislocated.

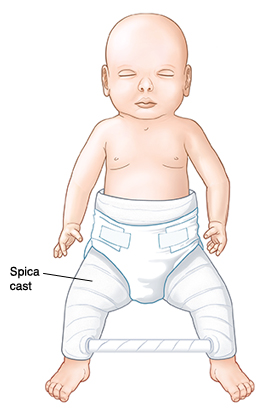

Casting. If your child still has DDH, a cast may help. This is called a spica cast. It holds the position of the hip joint.

Surgery. If the other methods don’t work, or if DDH is diagnosed at age 6 months to 2 years, your child may need surgery to realign the hip. Your child may then have to wear a spica cast for up to 6 months after surgery. This special cast holds the hip in place as it heals. After the cast is removed, your child may need a special brace or physical therapy exercises to strengthen the muscles around the hip and in the legs.

If DDH is found early, many babies do well with the Pavlik harness and, if needed, casting. Some babies may need one or more surgeries as they grow because the hip can dislocate again. If DDH is left untreated, a child may develop differences in leg length and a duck-like gait. Later in life, they may have pain or arthritis in the hip.

Key points about DDH in children

DDH is a health problem of the hip joint. The hip socket is shallow. This allows the head of the femur to subluxate or dislocate, slipping in and out of the socket.

DDH is present at birth. It may be caused by genetic problems and environmental factors.

A baby with DDH may have one leg that looks shorter than the other.

Newborns are screened for DDH before they leave the hospital.

Treatment may include a Pavlik harness, casting, or surgery.

Next steps

Tips to help you get the most from a visit to your child’s healthcare provider:

Know the reason for the visit and what you want to happen.

Before your visit, write down questions you want answered.

At the visit, write down the name of a new diagnosis and any new medicines, treatments, or tests. Also write down any new instructions your provider gives you for your child.

Know why a new medicine or treatment is prescribed and how it will help your child. Also know what the side effects are.

Ask if your child’s condition can be treated in other ways.

Know why a test or procedure is recommended and what the results could mean.

Know what to expect if your child does not take the medicine or have the test or procedure.

If your child has a follow-up appointment, write down the date, time, and purpose for that visit.

Know how you can contact your child’s healthcare provider after office hours. This is important if your child becomes ill and you have questions or need advice.

Connect with us:

Download our App: